Jeff Wayne - Horsell Common and the Heat Ray

Even in its abbreviated form the word “prog” is enough to raise my alertness level to twitchy. I’ve spent a good deal of my life on the run from its near-ubiquity. I’ve done all I can not to get sucked into its vortex of pomp. I’ve resisted, mostly, its ridiculousness. At times, listening to prog reminds me of Niles Crane’s feelings while learning to dance: “This is boring yet difficult”.

I know that, at least in part, my stubborn refusal to step into its world stems from that time in the early ‘90s when I was very deliberately seeking out obscure (in the context of my life at the time) indie music. All around me, it seemed, were fans of the rock gods. There was a mystifying desire to own albums that were fifteen to twenty years old. There was Pink Floyd, Pink Floyd everywhere, and I just wanted Ride and The Boo Radleys.

Mostly all this Floyd came in the form of The Dark Side of the Moon, an unstoppable juggernaut of an album that came neatly packaged within its own mythology. (Hey, wanna watch the Wizard of Oz with me?)

I’d tinkered a little with the album when I was young, having found it among the forbidden territory of the record collection. It had its moments: the cacophony of clocks that preface Time was either brilliant or maddening, possibly both; Money was like a nursery rhyme with some beats missing, although when I think of it now I’m more likely to drift off into the theme music for “Are You Being Served?”.

Listening to it now, it’s clearly not quite the big scary monster I’d allowed it to become in my imagination, just a world of music I wasn’t interested in at the time. I can hear echoes of all sorts of music that I love in fragments of songs like Us and Them and born in a different era I might have had the same dumbstruck reaction listening to Breathe (In The Air) that I had experiencing OK Computer for the first time.

“Woah, woah - wait a minute”, I can hear actual prog fans saying. “Just goes to show what you know about prog. Dark Side of the Moon is hardly representative of the genre, you know. It’s just big, bold, stadium-sized rock with spacey production”. To which I would say something like “look, you’re not exactly helping yourself here, ok?”. Because if that bête wasn’t prog enough for you, then the true animal must be bigger, uglier, longer (The Dark Side of the Moon checks out after a relatively spritely 43 minutes) and prone to moving in an ungainly fashion on account of its constantly shifting time signatures. While lumbering about, hampered by its lopsided gait and mobile center of gravity, the prog beast, you can be sure, will assert its intellectual superiority over the rest of the musical world as often as possible, using a series of clumsy metaphors and pseudo-philosophy.

Note, however, that not all the negative characteristics of prog are present all the time. When they are, we call this Genesis.

In the spirit of openness and honesty, I suppose I should admit that there are some modern artists that you might call progressive but who have caught my ear. Take this two track suite, Like the ocean, like the innocent, from The Besnard Lakes, which made it onto my year-end compilation in 2010:

http://youtu.be/Qs1P1Z7acW0

But back in the day, there really was some silliness at play. Take Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s 1977 song Fanfare for the Common Man. Aaron Copland apparently loved this version of his work, but to me it’s the sound of amplified nonsense, quickly knocked out to be the theme music for a minor sports highlights reel.

Still, it could be worse, I suppose. And I know this from personal experience, having been subjected to Hooked on Classics to a degree that makes me wonder what past life misdemeanours I must have been guilty of.

It all seemed so soft and tranquil…

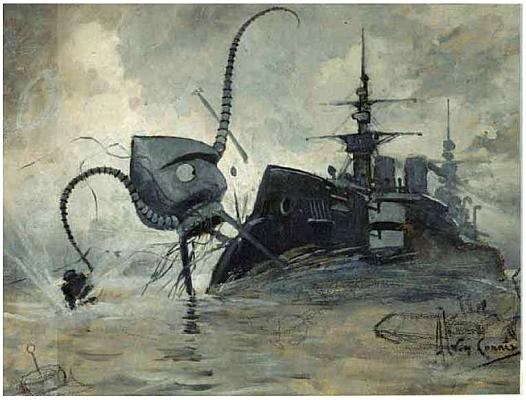

There was one prog album that I was open to, though. In 1898 H.G.Wells’ story The War of the Worlds was published; it’s the original steampunk nightmare, in which an unnamed narrator recounts the story of a Martian attempt to settle in the London commuter belt invade the earth via London and Surrey. Eighty years later in 1978, it was turned by Jeff Wayne into an ambitious rock opera featuring such diverse talents as David Essex and Richard Burton.

No-one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that human affairs were being watched from the timeless worlds of space…

Musically, War of the Worlds is prone to many of the usual tropes of progressive rock, from the bizarre disco n sound effects department stylings of opening number The Eve of The War to the conflation of electronic orchestral rock and Richard Burton’s narrative in his role as the journalist. But on this occasion it was the very combination that made it so compelling: the music enhanced the story; the story brought the music to life.

Its best known moments are perhaps Forever Autumn, which reached the top five in August 1978, and The Eve of the War, with its probability-baiting lyric:

The chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one” he said.

“The chances of anything coming from Mars are a million to one…

but still they come!”

If you’re a Terry Pratchett fan I don’t need to tell you of the deterministic flaw at play here.

The album includes various recurring leitmotifs. A leitmotif is a musical term used to indicate that you are listening to a serious piece of proper music. Here it’s employed to remind you of characters, locations, and the otherworldliness of the Martian invaders.

One of the motifs, an eerie six-note passage consisting of three descending couplets, bridges the end of The Eve of the War and the start of Horsell Common and the Heat Ray. This latter track is responsible for one of my more terrifying musical memories. In still darkness, enjoying an illicit late-night listening session, I lay transfixed by the irregular heartbeat and the rumbling bass that mark the moment one song becomes the other. They were joined by an inhuman breathing sound that seemed to come from somewhere else in the room, or everywhere in the room, as it jumped out of my headphones.

Having ascertained that I was, in fact, quite alone, I regained my composure, and continued listening. The opening passage of psychological terror is followed by brief respite in the form of non-threatening guitar work and waka-waka and what I can only assume is the sound of a jelly being struck with varying degrees of effort. Before long Burton is back, accompanied by the six-note motif and an early twenty-first century polyphonic ringtone, which in turn gives way to a terrific distorted guitar melody. Somewhere in the background, a guitar store employee attempts to impress a girl with his nimble fretwork. Then: more jelly, more waka-waka, more Burton, and fade with eerie six-note motif.

Effortlessly ridiculous as prog could be, and as clunky as other parts of The War of the Worlds sound to me now, this first section of the track, and the lead up to the crash of the lid as it falls still give me slight palpitations today, even in broad daylight, with an escape route planned.

Image attribution

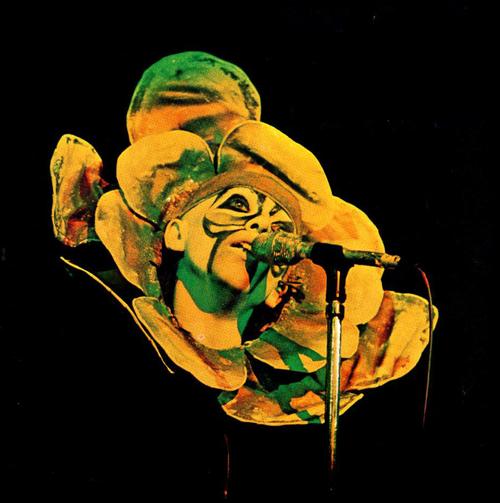

“Emerson moog” by Surka{.new} - Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Correa-Martians vs. Thunder Child” by Henrique Alvim Correa{.extiw} - drzeus.best.vhw.net. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.